The correlation between amount of sleep and performance in school

Abstract:

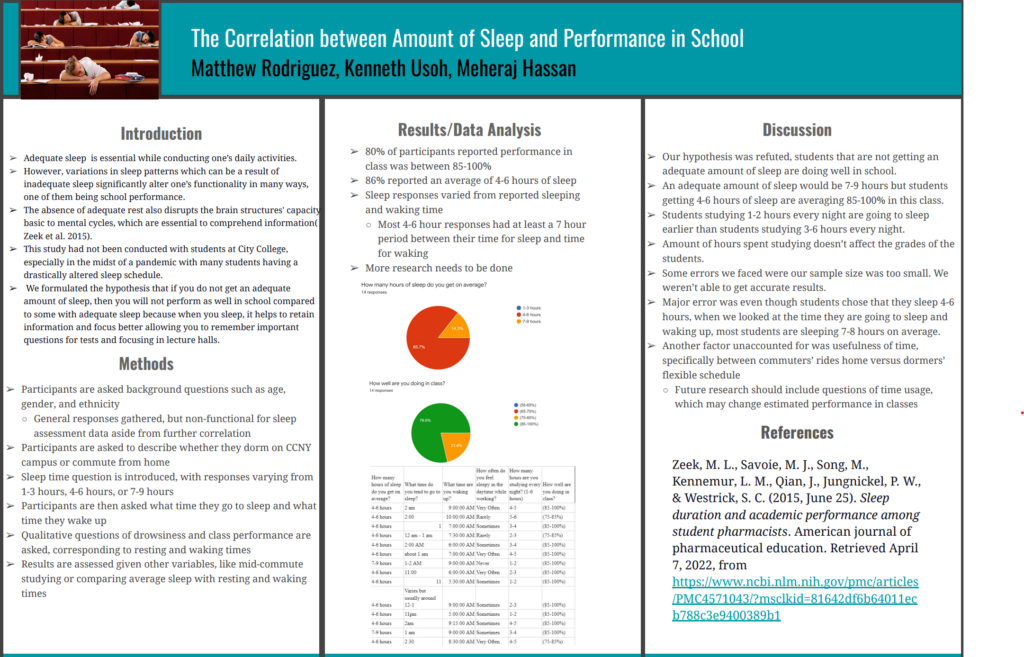

The objective of this experiment was to test if there was a correlation between the amount of sleep and performance in school amongst students at City College. The research was conducted through the means of a survey that contained questions that were both quantitative and qualitative. The survey was completely anonymous and was given to a range of first-year college students to college seniors. It gauges various aspects of factors that can affect sleep, such as if one is a commuter or not and other questions. Based on the information collected in Figure 1, 86% of participants reported that they rested an average of 4-6 hours every night. In Figure 2, 80% of participants said that their performance in class was between 85-100%. This part of the experiment contradicts the hypothesis. Instead, it is discovered that students who relatively recorded feeling drowsiness sometimes were still scoring well in their classes. To conclude, students at City College were receiving less sleep than the recommended amount of seven to nine hours of sleep but were still scoring well in their classes. Some limitations include having a small sample size that did not allow for a broader view of a more accurate trend of what is understood to be sleep and academic performance having a relationship.

Introduction:

Sleep has always been a necessity for people to be able to function while conducting their daily activities. However, variations in sleep patterns can significantly alter one functionality in many ways. One of them being performance in school. Being able to focus on completing assignments is helpless to deficient rest lengths, which are characterized as less than 7 hours every day for adults. Inadequate rest diminishes general readiness and debilitates consideration, bringing about eased back mental handling. The absence of adequate rest also disrupts the brain structures’ capacity basic to mental cycles, which are essential to comprehend information( Zeek et al. 2015). This study had not been conducted with students at City College, especially in the midst of a pandemic with many students having a drastically altered sleep schedule. This study is essential to determine how students’ performance is affected by their amount of sleep. Through this background information, we formulated the hypothesis that if you do not get an adequate amount of sleep, then you will not perform as well in school compared to some with adequate sleep because when you sleep, it helps to retain information and focus better allowing you to remember important questions for tests and focusing in lecture halls.

Methods:

To gauge participant response, given the college student target population, the best procedure would be to form a survey, proposing quantitative questions about the amount of sleep students get, how these students perform in their classes, and a specialized question to distinguish students who dorm on campus and students who commute to campus. The question of dorming versus commuting prompts the idea of a difference in sleep duration because of extenuating factors such as public transportation schedules; students who dorm naturally would never need to account for such things as subway times, considering their relative closeness and accessibility to their classes. Additionally, questions should be asked about when these students sleep when they wake up and how much time they study within a weekday or Sunday. Further questions may be asked about students’ background, places of residence, and age, all information that might pertain to students’ commute time or average duration of sleep.

First, participants are asked background questions such as age, gender, and ethnicity. With the generality presented with the first few questions, participants are then asked to distinguish whether they are dorming on campus or commuting from home and with the latter, from which borough they are commuting from. Then, the question of sleep time is introduced, where the only possible responses are 1-3 hours, 4-6 hours, or 7-9 hours. Participants are next asked what time they prepare to sleep and in a rough estimate of when they sleep; feedback should be open responses. The participants might have varying schedules depending on their dormer or commuter status. A subsequent question should be asked about participants’ waking time, although answers to this question should be limited, given that most students within the surveyed population attend early-morning classes. Questions regarding participant daytime behavior are given last after the quantitative data to collect qualitative data to support the hypothesis. Qualitative questions include, but are not limited to, measures of sleepiness of the individual and performance in class using adjectives rather than number-base. Some quantitative questions are matched with qualitative questions–the latter of the two questions posed previously as one example–to assess differences in participant response with reasonable data. Participants are asked questions of qualitative self-assessment and quantitative self-assessment, and the responses provided are the core of the resulting data.

Results:

As in Figure 2, Almost 80% of participants reported that their performance in class was between 85-100%. Similarly, around 86% of participants reported that they’ve rested an average of 4-6 hours every night in Figure 1. The information contradicted the hypothesis, but, as shown in Chart 1, sleep responses varied from the reported sleeping and waking time durations, where most of the 4-6 hour responses had a duration of 7+ hours. The information, then, had not been accurate to the hypothesis because of confusion in responses.

Figure 1: Average Sleep Responses

The above figure examines the response variation to the question of average sleep time. Note above how the listed choices are only general ranges, which most suspect they attain nightly but may vary compared to actual sleep time and wake-up time gathered.

Figure 2: Performance in Class

The above chart demonstrates the variation in performance between participants in the survey. Most individuals score their class performance naturally high, which might be an overestimation for some, but cannot be said to be for all participants. Real scores may vary, particularly with each class a participant may be taking.

Chart 1: Total Collected Data of Sleep Times and Performance

The table below explores the total data gathered from participants in the survey. Note that the most common response to the extent of daytime sleepiness is “sometimes,” Many participants correspondingly noted their sleep time most often between at least 1 hour of sleep and at most 5 hours of sleep. Also of note is that for every “sometimes” submitted, participants’ scores were between 85-100%, indicating some level of drowsiness is a standard for most student participants.

| How many hours of sleep do you get on average? | What time do you tend to go to sleep? | What time are you waking up? | How often do you feel sleepy in the daytime while working? | How many hours are you studying every night? (1-6 hours) | How well are you doing in class? |

| 4-6 hours | 2 am | 9:00:00 AM | Very Often | 4-5 | (85-100%) |

| 4-6 hours | 2:00 | 10:00:00 AM | Rarely | 5-6 | (75-85%) |

| 4-6 hours | 1 | 7:00:00 AM | Sometimes | 3-4 | (85-100%) |

| 4-6 hours | 12 am – 1 am | 7:30:00 AM | Rarely | 2-3 | (75-85%) |

| 4-6 hours | 2:00 AM | 6:00:00 AM | Sometimes | 3-4 | (85-100%) |

| 4-6 hours | about 1 am | 7:00:00 AM | Very Often | 4-5 | (85-100%) |

| 7-9 hours | 1-2 AM | 9:00:00 AM | Never | 1-2 | (85-100%) |

| 4-6 hours | 11:00 | 6:00:00 AM | Very Often | 2-3 | (85-100%) |

| 4-6 hours | 11 | 5:30:00 AM | Sometimes | 1-2 | (85-100%) |

| 4-6 hours | Varies but usually around 12-1 | 9:00:00 AM | Sometimes | 2-3 | (85-100%) |

| 4-6 hours | 11pm | 5:00:00 AM | Sometimes | 1-2 | (85-100%) |

| 4-6 hours | 2am | 9:15:00 AM | Sometimes | 4-5 | (85-100%) |

| 7-9 hours | 1 am | 9:00:00 AM | Sometimes | 3-4 | (85-100%) |

| 4-6 hours | 2:30 | 8:30:00 AM | Very Often | 4-5 | (75-85%) |

Discussion:

Our results show that the hypothesis wasn’t correct. An adequate amount of sleep for an adult is 7 – 9 hours, but from the results we gathered, we notice a common pattern that students getting 4-6 hours of sleep are doing well in school. We also noticed that most students spend 1-6 hours studying every night. The hours a student spends studying didn’t show an effect on their grades, but another common pattern we did notice is students who spend 3-6 hours studying every night are going to sleep later than students that are spending 1-2 hours studying. On average, students that study 1-2 hours are going to sleep around 11 pm, and students who are studying 3-6 hours are going to sleep from 1-2 am. Another observation we made was there’s no correlation between the amount of sleep a student is getting with how often they feel sleepy during the day. It seems like most students are sometimes, rarely, or very often sleepy during the daytime regardless of how much sleep they are getting.

Some errors we faced were not having specific sample sizes. Our sample sizes were too small, which made it harder for us to get accurate results. If we had a bigger sample size for the amount of sleep students are getting and a larger sample size for the grades, we could’ve got a more accurate result.

A major error we faced was, even though a lot of students chose to sleep from 4-6 hours, after we looked at the time they are going to sleep and the time they are waking up on average we noticed that most students were actually getting 7-8 hours of sleep. Overall the experiment was a success. Even though our hypothesis wasn’t correct, we still got to explore and understand more about the correlation between how sleep can affect a student’s academic performance.

References

Zeek, M. L., Savoie, M. J., Song, M., Kennemur, L. M., Qian, J., Jungnickel, P. W., & Westrick, S. C. (2015, June 25). Sleep duration and academic performance among student pharmacists. American journal of pharmaceutical education. Retrieved April 7, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4571043/?msclkid=81642df6b64011ecb788c3e9400389b1